A Hat Full of Candy and Chocolate

The horrors of war surrounded her: bombed-out buildings, smoldering barricades, the rumbling sound of planes, artillery fire, troop trains, and tanks; wounded soldiers, corpses, and panic-stricken families searching for lost loved ones; and as far as the eye could see, thousands of desperate and frightened refugees.

But for five-year-old Rhee Mai-ja, a beautiful, bright-eyed Korean girl who had fled with her family from Seoul in December 1950, the war was the “best and happiest time of my life.”

While millions of civilians and soldiers perished, Mai-ja was enjoying her childhood. She was free. She could do almost anything she wanted. She spent her days with her younger cousin cooking meals, running errands for her mother, and occasionally even eating fried grasshoppers with a neighborhood boy. “They’re actually quite delicious,” she said years later.

More importantly, for the first time in her life she didn't hear the dreaded words, “You should have been a boy!” No one was criticizing her for being a daughter. No one was telling her she should have been the son her parents so desperately wanted.

For Mai-ja, those were the “good” years.

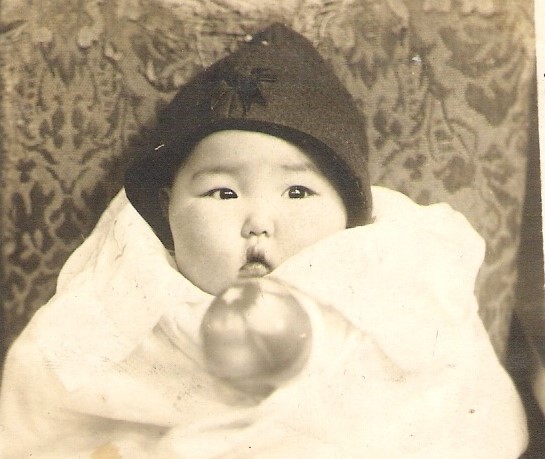

Maija as a baby, probably 100 days old, at adoptive parent's home. (Photo courtesy of Maija Devine).

Life in a Confucian Society

Months earlier, in a heart-wrenching decision, one that most people in a non-Confucian society would find hard to comprehend, Mai-ja’s father and mother, after fifteen years without a son, had reluctantly invited a woman into their home hoping she would conceive a male child. Mai-ja’s parents were in love and hated the idea of having another woman live with them, but without a son their family was at a great disadvantage both socially and financially.

Their plan worked. The family eventually had 4 boys and another daughter, but the emotional stress and trauma of the decision had a lasting impact, especially on young Mai-ja and her mother.

To make matters worse, years after the war ended Mai-ja found out that not only was she the daughter "who should have been a son," but she was not even her parents' birth daughter. She was adopted.

Born in 1943 to Korean parents who had moved to Manchuria during the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910-1945), Mai-ja was given up for adoption and sent to Korea. She was eventually taken in by the childless couple and for years was their only child. It wasn’t until she was an adult that Mai-ja learned the truth about her adoption and birth family.

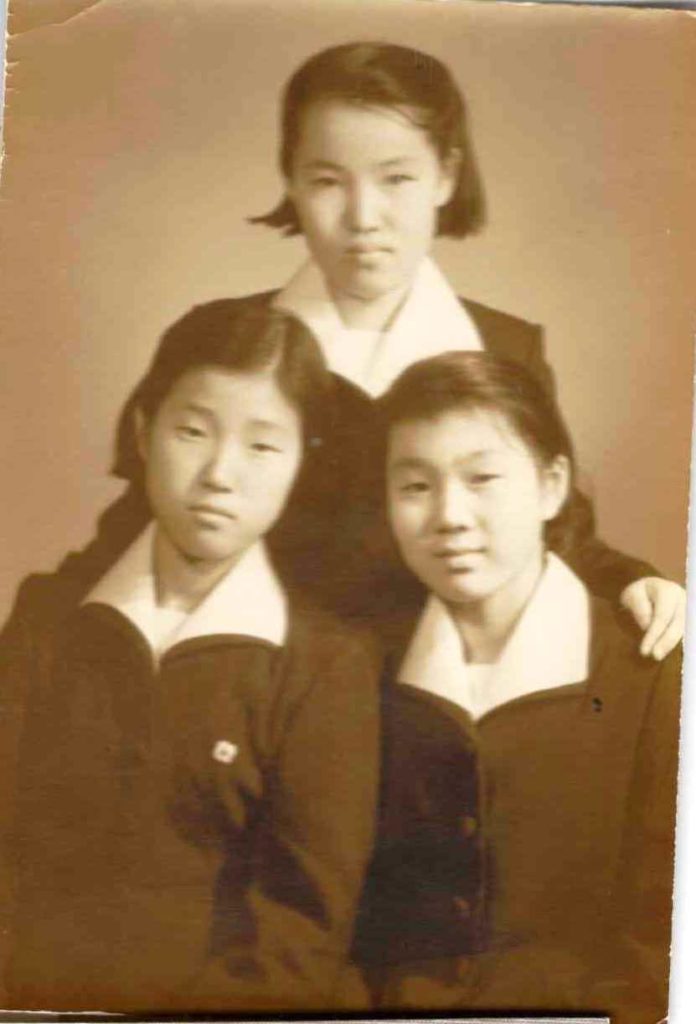

Maija's with her father (adoptive) at her graduation from Sogang University, 1965. (Photo courtesy of Maija Devine).

The Journey to Masan

In December 1950, after living in Communist-occupied Seoul for over three months and having suffered from harassment, indoctrination classes, the fear of being taken away by North Korean officials, and a late-night raid by Communist soldiers looking for rice and brassware, the family fled south to Masan, a town about 30 miles west of Busan.

Years later, Mai-ja would recall the harrowing trip. “My mother, grandmother, and I walked all day to god-knew-where along snow-covered frozen ground with thousands of people.” As women with babies strapped to their backs, old men and women carrying bundles and bags, and mothers and fathers guiding their children all made their way South, violence erupted. A bomb fell on the column of refugees, creating a huge explosion that caused “people to drop to the ground.”

“My mother pushed me down,” Mai-ja remembered, "and slapped her hands over my eyes.” It was not until decades later that she realized her mother was keeping her "from seeing what a child should not see."

When they finally arrived at a railway station, they boarded a train with thousands of refugees and were "crammed into pitch dark railroad cars that had no windows, chairs, and worst of all, no toilets.” After several days, they arrived in Masan. Mai-ja still remembers the miserable trip and how humiliating it was to relieve herself in open fields when the train stopped for brief bathroom breaks.

An American soldier gives a treat to a child during the Korean War. (Photo credit: US Army)

A Life-Changing Moment

After settling in Masan, the war seemed to disappear for the young Mai-ja. She reveled in her new life away from Seoul. One of the fondest memories during that time was the day she went to town with her mother and saw a train full of US soldiers.

Hundreds of children had swarmed the train, smiling and shouting, “Hello, G.I.” and “Give me candy, G.I.!” The soldiers, in turn, were laughing, joking and giving candy to the children. The more treats the Americans handed out, the more excited the children became.

Sitting with her mother on the other side of the street and feeling bashful, Mai-ja hesitated to get involved. She noticed a soldier looking at her and smiling, motioning for her to come towards him. She froze.

Mai-ja then watched as the man took off his hat and began asking his buddies for candy. Moments later, in an act of kindness that would have a profound impact on her life, he left the train, walked over to Mai-ja, and giving a friendly “Hello!” proceeded to pour the hat full of candy and chocolates into the little girl’s sweater pockets.

“I never could understand why out of all the kids at the train that day he gave the candy to me.” Her mother later said that maybe it was the hand-stitched red and green sweater she wore that made her stand out. “Maybe you reminded him of his daughter back home,” she added.

Regardless of the reason, the soldier’s generosity and thoughtfulness - and the delicious chocolate - made a lasting impression on her. “From that time on, I was determined to go to America.”

And she did. More than a decade after the war ended, she went to the United States and, except for brief stints in Korea, has lived there ever since. Throughout her life she’s never forgotten the horrors of the Korean War; she’s never forgotten her time in Masan; and she's never forgotten the American soldier who went out of his way to show her kindness and compassion.

"Some things always stay with you," she says.

Maija and Michael's wedding, Nov. 7, 1970, at Mary Hall Chapel, Sogang University campus. (Photo courtesy of Maija Devine)

Postscript

Mai-ja, now Maija Devine, graduated from Seoul’s Sogang University in 1965 and met Michael Devine, an American Peace Corps volunteer living in Korea, a few years later. They married in 1970 and relocated to the US, where they settled down and had five children.

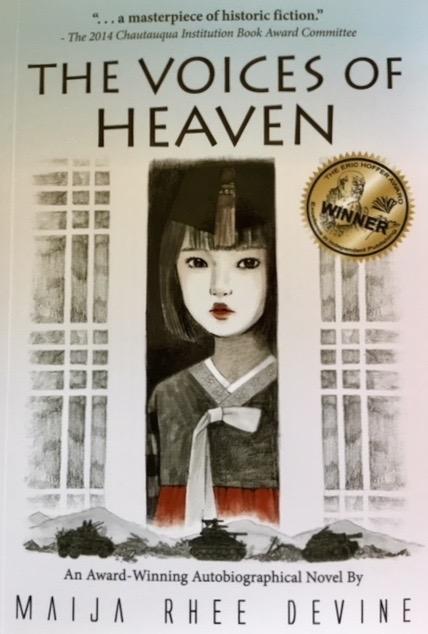

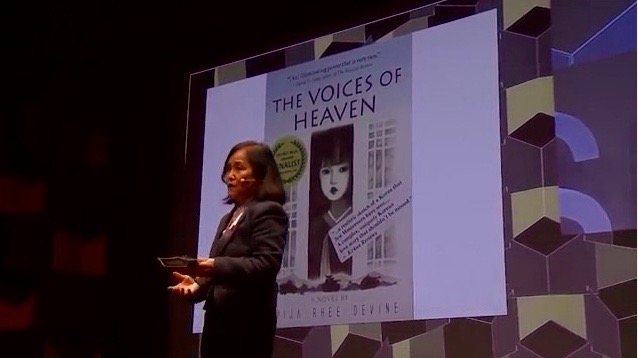

Maija spent ten years writing an autobiographical novel, The Voices of Heaven, based on her childhood and Korean War experiences. The award-winning book, filled with Korean proverbs, descriptive metaphors, heartbreaking stories of separation, pain, and sacrifice, and tales of redemption and forgiveness, is a highly praised and powerful account of the Korean War and life for an “average” family during that time.

Michael, the former Director of the Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri, and Maija, a frequent lecturer and advocate for women’s issues and the plight of World War II “comfort women,” have been married 48 years. They have four grandchildren and will soon be moving to Seattle.

Top/featured picture: Maija with her mom (adoptive), just before the Korean War broke out. (Photo courtesy of Maija Devine)

I will have to get this book. My wife was born right before the war, and had many similar experiences.

Thanks for reading the blog and commenting. Maija does a terrific job telling this story, and I hope that you’ll enjoy reading her book.