Doolittle Raiders: Mission Completed

Seventy-seven years ago today, one of the most storied and dangerous bombing missions of WWII began. The Doolittle Raiders, as the 80 men in the top-secret mission were called, were on their way to strike a blow at the heart of the Japanese empire: Tokyo.

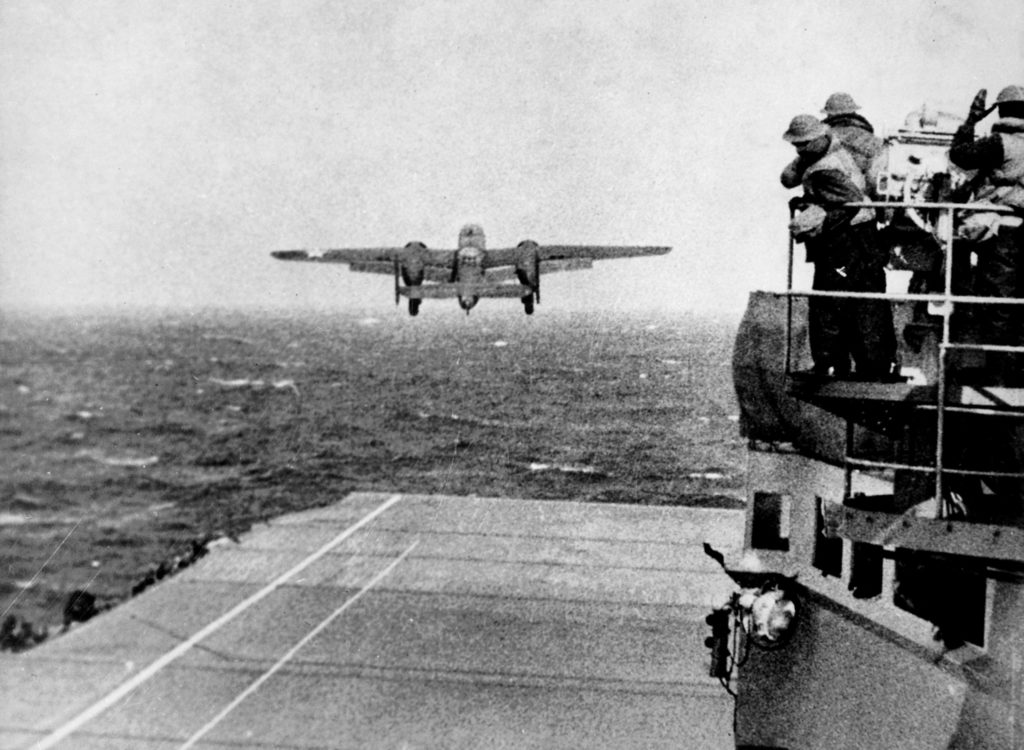

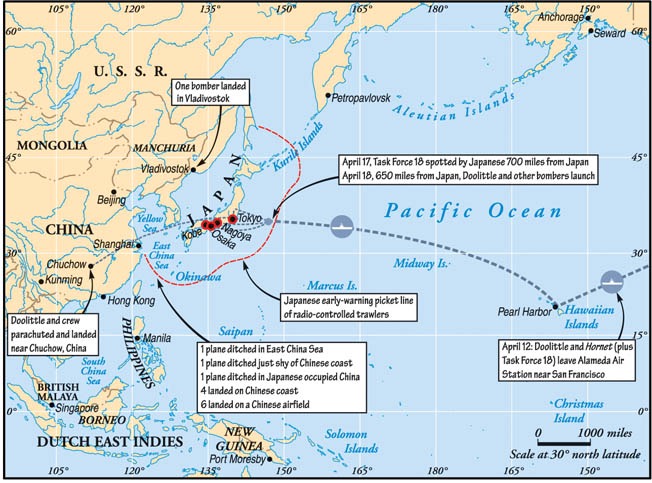

On April 18, 1942, as the first of 16 Army Air Corps B-25 bombers took off from the USS Hornet’s crowded flight deck, all eyes were on pilot and mission leader Lt. Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle and his co-pilot, Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Cole. The two officers, accelerating down the runway on their first ever flight off a carrier, had trained together for nearly seven weeks preparing for the highly dangerous mission.

If all went well, the men would fly stripped-down and modified B-25s across 600 miles of ocean, drop their bombs on designated military and industrial targets in Tokyo, and then, running low on fuel, land at airfields in China - or in the worst case scenario, crash land or bale out - and hopefully reach friendly lines without being captured or killed by the Japanese. The chances of making it home alive looked slim at best.

When Doolittle first revealed the specifics of the secret, high-risk mission to his men and explained the likelihood of some of them being killed or captured, he told them that anyone who so desired could honorably leave the unit and replacements would be found. None of the airmen bowed out.

Doolittle Raiders, Crew No. 1, 34th Bombardment Squadron. From left to right: Lt. Henry A. Potter, navigator; Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, pilot; SSgt. Fred A. Braemer, bombardier; Lt. Richard E. Cole, copilot; SSgt. Paul J. Leonard, flight engineer/gunner on the deck of USS Hornet, April 18, 1942. (PC: USAF)

If Anyone Was Scared, It Didn't Show

Six hours into the mission, all 16 planes, flying just 200 feet above the ocean to avoid radar detection and with no fighter escorts, reached Tokyo and in broad daylight began dropping their bombs. Cole later recalled in an Air Force interview, “Everyone prayed but did so in an inward way . . . if anyone was scared, it didn’t show.”

The Japanese were caught totally by surprise. “People on the ground waved to us. We could see the moat, the Imperial Palace and downtown Tokyo,” Cole remembered.

Although the bombing raid had little effect on Japan’s industrial output, the daring mission, which had its origins in President Roosevelt’s desire to retaliate for the attack on Pearl Harbor, sent shock waves through the Land of the Rising Sun.

For the Japanese, who had been told their capital was invulnerable to US attack, the Doolittle Raid was a huge psychological blow and harbinger of things to come. For the Americans, the raid was a tremendous morale boost during the darkest days of the war.

Doolittle (pilot) and Cole (co-pilot) and their three crewmembers are the first to take off from the Hornet. (PC: US Navy)

The Aftermath

After hitting their targets, fifteen of the planes, running on fumes, made it to China, where they crash-landed or their crews bailed out. One plane landed in Vladivostok, where its crew was taken prisoner by the Soviets but eventually allowed to “escape.”

Of the 77 Doolittle Raiders who survived the initial stage of the mission, the Japanese captured eight; three were later tried and executed and one died of malnutrition and disease.

The remaining airmen, including Doolittle and Cole, avoided capture and with the help of Chinese civilians and military officials they eventually reached American authorities. The four surviving POWs, after enduring more than three years of brutal treatment, were freed by US troops at the war’s end.

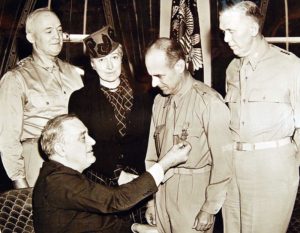

Jimmy Doolittle receives the Medal of Honor from President Roosevelt. Standing, (L–R) Lt. Gen. H.H. Arnold, Josephine Doolittle, and Gen. George C. Marshall. (US Navy)

Doolittle, who initially believed the mission had been a failure and that he would be court-martialed for losing all 16 of his aircraft, was awarded the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous leadership above the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life.”

The raid was later immortalized in the 1944 Hollywood movie, “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” based on the book by Raider pilot Ted Lawson.

Postscript

Dick Cole, Doolittle’s co-pilot and the last surviving member of the Doolittle Raiders, went on to fly transport planes over the Himalayas in the China-Burma-India Theater and serve during the Korean War. He retired from the Air Force as a Lt. Colonel in 1967. During his legendary career he earned three Distinguished Flying Crosses and accumulated over 5,000 flight hours in 30 different aircraft.

Cole died on April 9, 2019, at the age of 103. He will be remembered today at a memorial service in Texas, 77 years to the day that he flew on the historic mission.

Dick Cole with Gary Sinise a few years ago. (PC Gary Sinise)

Feature/top picture: B-25 takes off from the USS Hornet for Tokyo, April 18, 1942. (PC:US Navy)